Bless You

Galit Litani

In medical science health is often defined as the ability of the body to maintain its internal stability by means of balancing external influences such as heat, cold, bacterial activity, injuries etc. In order to assist the body in staying healthy man took a variety of measures that constituted the beginnings of medicine.

In prehistoric times, man learned by experimenting and pondering the effect of plants and minerals on a variety of injuries. This experience was passed down from generation to generation and was refined as folk medicine that also included an appeal to divine powers that were believed to be responsible for sickness and healing.

Institutionalized medicine was already taught in ancient Egypt and Babylonia; however, Hippocrates, the ‘father of medicine’ who lived in Greece in the fifth century BCE, is considered the founder of modern scientific medicine. The method of treatment he practiced is based on observation, experimentation and rational scientific explanations, and the concept that disease is a natural phenomenon and not divine punishment.

Sorcery and Medicine

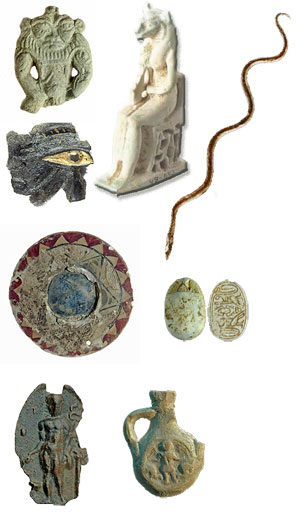

In pagan societies certain gods were charged with the responsibility of health or illness. Asclepius was the god of medicine in Greece and Rome and his symbol, the caduceus, is also the symbol of medicine today. The snake depicted on the caduceus is considered a magical animal possessing healing powers and was used as both an amulet and a medicinal ingredient.

Written charms and spells were some of the most common ways for a person to deal with sickness and avert ill health. Spells were written on papyrus, bowls, scrolls and plaques, the purpose of which was to banish the harmful entity from the patient or to summon protective powers.

Demons, ghosts and satyrs are mentioned in the Bible, as well as in the Talmud and Kabbalah, but the treatment and sickness are always in the Lord’s hands, and it is he according to Jewish belief that afflicts us with disease and heals us. Although the use of sorcery was forbidden and considered idolatry, the use of healing spells and amulets was permitted with certain restrictions.

Hygiene

The word hygiene is derived from the name of the goddess of health Hygieia, daughter of Asclepius – the god of medicine. Disease prevention was a common way of safeguarding good health in antiquity and it was mostly accomplished by maintaining personal and public hygiene.

Personal hygiene included for example, preventing the infestation of parasites in one’s hair by means of shampooing, combing and oiling or applying kohl eyeliner to one’s eyes to protect them from flies, drying up and the desert light.

Washing one’s body was common as attested to by the story of Bathsheba bathing herself on the roof. In certain cultures bathing was anchored in religious commandments and appeared mostly in connection with ritual purification or after an illness.

Public bathhouses that have their beginnings in ancient Greece reached the height of their development in the Roman world where toilets were built in them for the public’s benefit. Similar toilets were also found in private homes dating to the First Temple period, in the City of David in Jerusalem.

Sewer and drainage systems were incorporated in ancient cities and in medieval times it was customary to use chamber pots similar to those used today.

Many of the commandments in the Bible are related to afflictions, impurity, purity and dietary laws, which apart from their being a divine commandment they have an obvious hygienic aspect. The rabbinic sages also addressed this matter at length.

Hippocrates the Greek and Maimonides practiced preventive care that relates to diet, exercise, hygiene and rest.

Means of Treatment

Evidence regarding the methods used for treatment is found in the scriptures, archaeological finds and the remains of bones. Chronic and traumatic injuries that had healed were discerned on the skeleton of a Neanderthal man from 70,000 years ago which was discovered in Iran. It seems that this is evidence that the society in which the man lived looked after him until he recovered. Invasive medical intervention is evidenced in trepanation, a procedure that involves piercing the skull for medical purposes, such as relieving pain, and for mystical purposes in order to release demons; trepanations were conducted as early as c. 7,000 years ago. Descriptions of medical instruments appear in the tombs of Egyptian and Roman physicians, as well as in Greek and Roman literature, and they include a wide variety of scalpels, bone spreaders, forceps, and curettes for removing foreign bodies.

The most common means of treatment were a variety of natural substances. The most famous medicinal herb in the Bible is balm, which Rabbi Saʽadia Gaon identified as an ingredient in the serum against poison; asphalt from the Dead Sea was used for treatment and mummification.

Drugs are mentioned in rabbinic literature, including parts of animals that are not considered kosher such as snake.

Spas were also used for natural healing. The ancients were familiar with the unique properties of hot water springs for relieving the body and mind and as a treatment for rheumatism, skin diseases, weakness, nervous disorders and sexually transmitted diseases. In addition to natural substances they would also use other means such as cupping glasses which were used in Greece as early as the third century BCE.

Healers and Doctors

The biblical concept that the Lord is the supreme healer characterizes the reference to a doctor in a negative context. This attitude is also found in the Mishnaic dictum that says, “"The best among the physicians to Gehinom (to hell)" (Kiddushin 4:14). The Tannaim took a more lenient approach in saying, “Virofeh yirapeh” (meaning the physician will heal) – that is to say the doctor has permission to practice medicine and the halacha even considers the medical profession a mitzvah, although the doctor was always thought to be an messenger of God.

Specialization in the different fields of medicine was already being practiced in ancient Egypt, as evidenced by the Greek historian Herodotus: “The art of medicine among them is distributed thus:--each physician is a physician of one disease and of no more…..for some profess themselves to be physicians of the eyes, others of the head, others of the teeth, others of the affections of the stomach, and others of the more obscure ailments”. We know that in Rome and Greece there were doctors who specialized in dentistry, ophthalmology and gynecology. There were also sectoral doctors such as the royal physician, military doctor, public doctor, a doctor for slaves and a doctor for free people.

Titles such as chief physician, senior physician or commissioner of physicians reflect the professional hierarchy that was practiced in Egypt, Greece and Rome.